Josiah Henson Museum of African-Canadian History

Street address

29251 Freedom Road (formerly Uncle Tom's Road)

Dresden, Ontario

N0P 1M0

Contact: Steven Cook

Telephone: 519-683-2978

Fax: 519-683-1256

Email: jhm@heritagetrust.on.ca

Hours

May 17 to October 24, 2025 — Wednesday to Saturday, 10 a.m. to 3 p.m.; Sunday, Noon to 3 p.m.

School and groups of 15 or more can be pre-booked by email or phone year-round.

Emancipation Day 2025: Saturday, August 2

Admissions (HST included):

Adults: $9

Seniors: $7

Students (aged 13-17): $7

Children (aged 6-12): $5

Children under 6: Free

After escaping to Upper Canada (now Ontario) from slavery in Maryland and Kentucky, Josiah Henson established himself as a conductor on the Underground Railroad, travelling the clandestine network of paths and safehouses in reverse. In his role as conductor, he rescued 118 enslaved people.

A strong proponent of education and self-reliance, Henson relocated to Dresden, Ontario in 1841 and co-founded the British American Institute of Science and Technology with Oberlin, Ohio missionary Hiram Wilson. The settlement — known as Dawn — developed around the school. Its residents farmed, attended the Institute and worked at sawmills, gristmills and other local industries. Some returned to the United States after emancipation was proclaimed in 1865. Others remained, contributing to the establishment of a significant Black community in this part of Ontario.

Known as “Uncle Tom” through his connection to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 anti-slavery novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Josiah Henson was one of the most famous Canadians of his day. Henson's celebrity raised international awareness of Canada as a haven for refugees from slavery.

The Josiah Henson Museum of African-Canadian History recognizes the accomplishments of Josiah Henson through interpretive videos, interactive exhibits, numerous artifacts and tours that reflect the Black experience in Canada. The two-hectare (five-acre) site consists of the Josiah Henson Interpretive Centre, with its Underground Railroad Freedom Gallery and North Star Theatre, plus three historical buildings – including the Josiah Henson house – two cemeteries, a sawmill and numerous artifacts that have been preserved as a legacy to these early pioneers.

Throughout the year, the site hosts many fascinating programs and activities. For example, each August Civic Holiday weekend, the site hosts Emancipation Day with various speakers, performers, exhibits and cuisine that reflect early Black life in Ontario. In addition, Black History Month programming takes place each February, as well as a Diversity Dialogue retreat for youth in the spring and an annual workshop for educators on how to incorporate Canadian Black history into their curriculums.

The museum is owned and operated by the Ontario Heritage Trust.

Early years

Josiah Henson was born into slavery in Charles County, Maryland about 1796. During his enslavement, he was separated from loved ones and endured unimaginable abuses. He was once beaten so badly at the hands of an overseer that both his shoulder blades were broken. As a result of these injuries, he was maimed for life. Throughout this time, Henson found comfort in his faith and the Methodist church. He began preaching and was eventually ordained a minister. In 1829, he arranged to purchase his freedom with the money earned from his preaching. But he was betrayed by his master and taken to New Orleans to be sold. He fled northwards along the silent tracks of the Underground Railroad to escape slavery.

Henson did not make the journey to freedom alone. He brought his wife and their four children, whom he would often carry on his back. The Henson family travelled on foot by night and hid in the woods by day. After a long and dangerous six-week journey, the Hensons arrived on the Canadian shore on the morning of October 28, 1830.

Henson quickly asserted his leadership as a preacher and conductor on the Underground Railroad. He worked with energy and vision to improve life for the Black community in Upper Canada (now Ontario). After this dramatic escape from slavery, “Father Henson” quickly attained the status of leader within the Underground Railroad community in southwestern Ontario.

The Dawn Settlement

Josiah Henson used his freedom to help establish the Dawn Settlement – a community where Blacks could share their skills, labour and resources to help each other and give aid to newly arriving settlers. This spirit of co-operation was embodied by the church, one of the Black community’s most important institutions. The church served as a place of worship and a centre for meetings, educational, recreation and social activities.

At the Dawn Settlement, crops such as wheat, corn and tobacco were harvested by the settlers. Locally grown black walnut lumber was also exported to the United States and Britain. A key element of the settlement was a vocational school co-founded by Henson – one of the first in Canada – that taught a variety of skills. Called the British American Institute, the school had access to the community’s farm land, sawmill, gristmill, brick yard and rope manufactory. The Institute opened in 1842 with a mandate to “cultivate the entire being, and elicit the fairest and fullest possible development of the physical, intellectual and moral powers.” Students would spend one part of the day in the classroom and another working at a trade. Items manufactured by the students were sold, with the proceeds going to the school. Female students learned domestic skills and male students worked at the mills or in the fields. A provincial plaque commemorates the Dawn Settlement and its many significant contributions.

Some members of the community returned to the United States after emancipation was proclaimed in 1863. Others remained, contributing to the establishment of a significant Black community in this part of the province.

The first edition of Henson’s autobiography was published in 1849 under the title The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada, as Narrated by Himself. Six editions would eventually be published, between 1849 and 1883. Harriet Beecher Stowe used Josiah Henson's memoirs as reference material for her 1852 novel, Uncle Tom's Cabin. Henson's dramatic experiences and his connection with Stowe's book made him one of the most famous Canadians of his day.

Rev. Henson died on May 5, 1883. He is buried adjacent to the Josiah Henson Museum of African-Canadian History in the Henson family cemetery. He had continued to preach in Dresden’s British Methodist Episcopal Church each Sunday until his death. Henson was survived by several children and his second wife Nancy Gambril. His first wife, Charlotte, predeceased him in 1852.

"I'll use my freedom well"

Josiah Henson was an important advocate in support of literacy and education for Black Canadians and a devoted fundraiser for the

Institute. He travelled across Canada, the United States and, on three occasions, to England, in search of donations. He was also a committed conductor on the Underground Railroad and frequently made the dangerous trip to slave-holding southern states to encourage and facilitate the escape of enslaved Blacks to Canada.

Although maimed early in life, he helped to defend this country as captain of a Black militia group stationed at Fort Malden during the Rebellion of 1837. Henson also helped Black Canadians to join the fight against slavery during the American Civil War. At least 1,000 men joined the Union Army in different Black regiments after the ban on Black soldiers was rescinded in 1862.

To the schooner captain that had provided him and his family safe passage across the Niagara River so many years before, Josiah Henson had promised, “I’ll use my freedom well.” Prophetic words from a man of action. Henson indeed used his freedom well. From

providing for his family to establishing a thriving community in the Dresden area, Henson leveraged his own personal freedom into widespread freedom for all who wanted it. In returning to the southern United States, Henson took the Underground Railroad in reverse. He risked everything – his years of work, his freedom, his life – to bring others north from bondage. Henson would eventually personally lead over 118 enslaved persons north – to a land of new opportunity, to freedom.

Be sure to visit the “I’ll use my freedom well” exhibit at the Josiah Henson Museum of African-Canadian History. Through featured artifacts, vivid imagery and interpretive panels, you will be given a fresh look at the life of Josiah Henson.

“It has been spread abroad that ‘Uncle Tom' is coming, and that is what has brought you here. Now allow me to say that my name is not Tom, and never was Tom, and that I do not want to have any other name inserted in the newspapers for me than my own. My name is Josiah Henson, always was, and always will be.” Josiah Henson, Glasgow, Scotland, 1877 (from Uncle Tom’s Story of His Life)

Uncle Tom’s Cabin Historic Site has changed its name.

In recent years, the Trust has conducted a focused review of its properties and programming. New research and the openness to diverse perspectives help to broaden our understanding of Ontario’s heritage, including the evolution of terminology.

The Trust recognizes the power of words in conveying emotions, values and memories. The term "Uncle Tom" carries several destructive stereotypes and harmful connotations that diminish and detract from Josiah Henson’s significant contributions to African-Canadian heritage and the broader Black community.

The term “Uncle Tom” is used in social media, television, movies and literature as a means of insulting and demeaning a person of Black heritage. It implies that a person of African descent is a traitor to their race and, as such, the phrase is perceived as pejorative and harmful, despite Harriet Beecher Stowe’s intentions in the creation of her literary character. To continue to use this term in association with Josiah Henson does a disservice to his legacy. Henson worked with energy and vision to improve life for the Black community in Ontario. By remembering him as Uncle Tom has, in some ways, diminished his status and accomplishments.

From its inception as a small Ontario tourist attraction in the 1940s to its status as a hub for Black recognition and accomplishment, the museum property and programming has continually evolved. Join us on this ongoing journey to freedom!

Here, you can better understand the evolution of the museum and its close association with the term “Uncle Tom.”

Stowe's Uncle Tom

Uncle Tom is the protagonist of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 anti-slavery novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Her portrayal of Tom was that of a stoic, noble character who humanized the suffering and hardships of enslaved people of African descent for its readers. In Stowe’s novel, the Tom character is presented as a virtuous figure, guided by his religious conviction of non-violence. Tom exhibits compassion and empathy despite the cruel treatment of his enslavers. He is portrayed as a leader and protector of those with whom he is enslaved, caring for them when they are injured or ill, and offering spiritual guidance to those whose own resolve weakens under the oppressive institution of slavery.

The trials that Tom endures throughout the novel are a testament to Stowe’s original vision for a sympathetic Black character that would bring attention to the mistreatment and dehumanization of enslaved people of African descent. Although Stowe's intent was to portray Tom as a symbol of strength, goodness and leadership, the negative connotation associated with Uncle Tom quickly shifted the way that he was perceived.

Becoming Uncle Tom

Henson's autobiography – The Life of Josiah Henson, formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada, as Narrated by Himself – was published in 1849. When southern plantation owners accused Harriet Beecher Stowe of misrepresenting slavery in her novel, she published, in 1853, Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Presenting the Original Facts and Documents upon Which the Story Is Founded, Together with Corroborative Statements Verifying the Truth. It was here that Stowe quoted extensively from Henson’s autobiography in the defence of her novel.

Henson's autobiography was expanded and republished in 1858 under the title Truth Stranger Than Fiction: Father Henson's Story of His Own Life. This edition contained a foreword by Harriet Beecher Stowe, which reinforced the public’s perception of Henson as the model for the character of Uncle Tom in her novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Henson rose to international prominence after Harriet Beecher Stowe acknowledged his memoirs as a source for her novel.

The Rise of Uncle Tom-ism

Minstrel shows developed in the United States in the 19th century as a form of stage entertainment but were popular across Canada and Europe as well. They showcased negative racial stereotypes with white performers putting on black face (darkening their skin with burnt cork or shoe polish) and performing racist songs, dances and comedy routines. Read more about the history of black face and minstrel shows in Canada.

Following the release of Harriet Beecher Stowe‘s internationally bestselling novel, minstrel show versions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin began popping up throughout North America and Europe as a response to the anger and embarrassment caused by Stowe’s depiction of plantation slavery.

These “anti-Tom” shows saw the central character of Tom transformed from that of a saintly figure to a fawning, docile and self-loathing yes-man, known for singing, dancing and smiling despite his dire circumstances. These performances sought to obscure the violence and inhumanity of the institution of slavery. “Tom shows” played for over 80 years before they finally died out in the 1930s, but their harmful legacy remains to this day.

Now, the term is used as an insult. It references a person of African descent who is considered a traitor to their race by seeking approval and attention from white people.

Preserving Henson's legacy

The house in which Josiah Henson spent the latter days of his life was first opened to the public as a tourist attraction in 1948 by then-property owner William Chapple, who named it “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” The house was later sold to Jack Thomson, who moved the structure and two other period buildings to their present location in 1964 with the goal of starting a museum. Thomson named the museum “Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Museum” after the novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly by Harriet Beecher Stowe, in which the character Tom was loosely based on the life of Josiah Henson.

In 1984, the site was sold to the County of Kent who transferred it to the St. Clair Parks Commission in 1992. In 1993 and 1994, the historical site underwent extensive upgrades and restoration of the three period structures, and the Josiah Henson Interpretive Centre was built, followed by a rededication ceremony in 1995. The site was renamed Uncle Tom’s Cabin Historic Site at this time. The property and buildings were transferred to the Ontario Heritage Trust in 2005.

Although discussions of a name change have happened since the early 1990s, the St. Clair Parks Commission, which managed the site at that time, in consultation with the Uncle Tom’s Cabin Historic Site Advisory Board, felt that the museum had a positive association with visitors from around the world who had studied the anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom's Cabin. More recently, the Trust has attempted to reclaim the phrase as it aligns with the anti-slavery movement and the fight against slavery. Through greater understanding of Canada’s role in systemic anti-Black racism, it is recognized that it is necessary to carve a path forward that is more equitable and just and it is the time to revisit the name “Uncle Tom’s Cabin Historic Site.”

Reclaiming Josiah Henson

Approaching his 80th birthday , Josiah Henson reflected on his life from a pulpit in Glasgow, Scotland as part of his tour of the United Kingdom. Once again, he was introduced to the thousands in attendance through his association with Stowe’s literary creation. It was his desire, however, to be acknowledged for his life’s remarkable achievements – as a conductor of the Underground Railroad and a force in the abolition movement, as an educator and co-founder of the British American Institute, as the author of his memoirs, which put Canada on the map as a safe haven for refugees from slavery, and as a preacher, husband and father.

The Ontario Heritage Trust strives to ensure that the heritage we protect and the stories we tell are respectful, accurate and authentic representations of the peoples who have lived on this land.

Much like the stories of other Blacks and African Canadians who have been obscured over time, the achievements of Josiah Henson have also been diminished. Separating Henson’s identity from the literary character of Uncle Tom allows us to reclaim the legacy of his life’s work and acknowledge the importance of this work in building an anti-racist and inclusive Ontario.

Book your virtual guided tour of the Josiah Henson Museum of African-Canadian History today!

After escaping slavery in 1830, Josiah Henson, with the help of other abolitionists, sought ways to provide refugees with the education and skills needed to become self-sufficient in Upper Canada (now Ontario). In 1841, they purchased 121 hectares (300 acres) of land in present-day Dresden and established the British American Institute, one of the first schools in Canada to emphasize vocational training. The community of Dawn developed around the Institute. The stories of these freedom seekers and how they contributed to the establishment of a significant Black community in this part of the province is told at the Josiah Henson Museum of African-Canadian History.

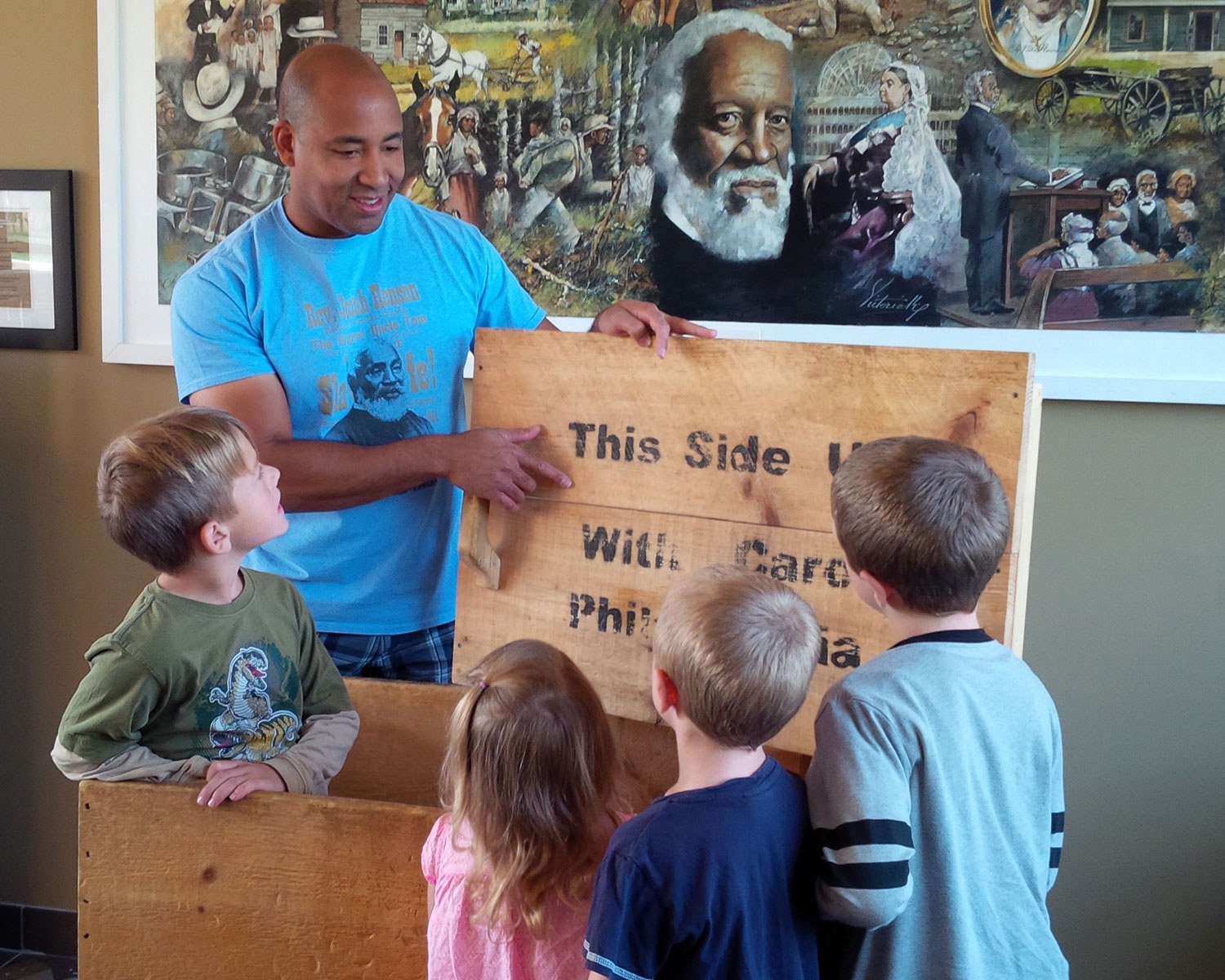

Designed for educators, this 45-minute live tour of the Josiah Henson Museum of African-Canadian History brings the history of the Underground Railroad to life through artifacts, a walking tour of the historical buildings, interactive activities and incredible storytelling. A brief question-and-answer session will follow each tour.

An estimated 30,000 Black refugees from slavery in the United States fled to Canada along the silent tracks of the Underground Railroad – a network of people who aided these refugees as they followed the North Star to freedom. One of these freedom seekers was abolitionist, Underground Railroad conductor and former slave Josiah Henson. He became known as Uncle Tom through his connection to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 anti-slavery novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Josiah Henson’s story is told at the Josiah Henson Museum of African-Canadian History in Dresden, Ontario. Your live-streaming experience incorporates a tour of the museum and two-hectare (five-acre) property, including the Interpretive Centre, three historical buildings – including the Josiah Henson House – a sawmill, two cemeteries and numerous artifacts that have been preserved as a legacy to those freedom seekers.

Topics discussed include:

- an overview of the trans-Atlantic slave trade

- slavery in Ontario

- a discussion on the life of Josiah Henson

- the Underground Railroad

- early Black settlements in Ontario

Book your live virtual guided tour today to meet a descendant of some of these courageous Underground Railroad freedom seekers and learn about the early Black presence in Ontario!

Note: For an optimal viewing experience, a stable internet connection capable of streaming high-definition videos on one or more devices is recommended.

You’ll be able to live-stream this tour using any standard web browser. For an optimal experience, we recommend that you use the latest version of your browser.

Portions of the tour discuss the harsh reality of slavery in a sensitive and honest manner and may not be suitable for all ages.

Duration of tour: 45 minutes

Maximum class size: 35 students

Minimum class size: 15 students

Note: Suitable for students in Grades 5 through 11

Black History Month

Black History Month is recognized throughout Canada, providing citizens an opportunity to reflect on and celebrate the contributions and achievements of Canadians of African descent.

The push for recognizing Black achievement began with American author and historian Carter G. Woodson who, in 1926, proposed an observance to honour the accomplishments of Black Americans. He called it Negro History Week, which was later renamed Black History Week. He chose the second week of February because it marks the birthdays of renowned abolitionist Frederick Douglass and United States President Abraham Lincoln, who is credited with the abolition of American slavery. In 1976, it was changed to Black History Month in the United States.

Through the efforts of the Ontario Black History Society, the House of Commons in Canada officially recognized Black History Month in 1995 when The Honourable Jean Augustine – the first Black female member of Parliament – introduced the motion. It was unanimously adopted.

NOTE: Beyond the Underground Railroad: The living legacy of Mary Ann Shadd Cary (videos now available)

2023 marks the 200th anniversary of the birth of Mary Ann Shadd Cary – a pioneer in publishing, education and law. Cary was the first Black woman newspaper publisher in Canada, established a racially integrated school for Black refugees in Windsor and, in 1883, she became one of the first Black women to complete a law degree in North America. Join the team behind the video series Beyond the Underground Railroad for an informative and educational discussion celebrating Cary’s remarkable life and legacy.

Beyond the Underground Railroad is an annual pre-recorded virtual discussion hosted by the Josiah Henson Museum of African-Canadian History, Buxton National Historic Site & Museum and the Black Mecca Museum. Watch previous videos: Strategies for confronting anti-Black racism (2022) and Black History in Chatham-Kent (2021).

Emancipation Day

Many communities in Ontario began celebrating Emancipation Day after the Abolition of Slavery Act became law on August 1, 1834. The day was especially popular in places where freedom seekers from plantations in the United States settled – most notably Sandwich (now Windsor), Toronto, Hamilton and Owen Sound. And, of course, the Dawn Settlement in Dresden celebrated as well.

In the 19th century, Emancipation Day was an important expression of identity for the Black community and anti-slavery activists. It gave people the opportunity to celebrate the end of slavery in Canada and the British Empire with parades, music, food and dancing. The day also provided a vehicle to lobby for Black rights in Canada and the abolition of American slavery.

Emancipation Day continues in Ontario today. In 2010, Windsor marked its 175th Emancipation Day. The Josiah Henson Museum of African-Canadian History has revived the spirit of emancipation and continues to celebrate Emancipation Day every year.

Josiah Henson Museum of African-Canadian History video library

Reflect on inspiring stories that speak to the early African-Canadian experience in Ontario through recorded interviews, presentations, pre-recorded virtual tours, performances and more.

Slavery to Freedom

Slavery to Freedom chronicles the perilous path that 19th-century Black people followed to find sanctuary in Ontario.

Heritage Matters: Stories about Black heritage

Enrich your understanding of our past and present with articles about Black heritage and history from across the province. Learn about exceptional individuals such as dance pioneer Len Gibson and the Honourable Jean Augustine or explore the history of Black women’s voting rights.

Provincial plaques: Celebrating Ontario’s Black heritage

Our provincial plaques commemorate important stories related to Ontario’s Black heritage – from War of 1812 soldiers and Underground Railroad conductor Harriet Tubman to churches and settlements that have carved out a place in Ontario’s story. Here’s a few to get you started:

- The Wilberforce Settlement

- The Buxton Settlement

- The Solomon Moseby Affair, 1837

- Chloe Cooley and the 1793 Act to Limit Slavery in Upper Canada

- William and Susannah Steward House

- Hugh Burnett and the National Unity Association

Explore more plaques and historical plaque background papers.